Cardinal Richelieu has long had a ‘bad press’. Demonized in successive Hollywood versions of The Three Musketeers, he is generally known to the public as a power-crazed villain, usually seeking to bring down the King and take the throne himself.

Vincent Price as Richelieu

To put it bluntly, this is not true. He was ambitious and unquestionably ruthless, but his energies seem only to have been devoted to the ultimate greatness of France. Even Alexandre Dumas does not question this, and those who actually read his novel will find his treatment of Richelieu fairly even-handed. The chivalrous Musketeers see him as a villain because he is attacking the integrity of the Queen – but the Queen was (according to Dumas) having an affair with Buckingham, who had already taken arms against Louis XIII at the Siege of La Rochelle. In modern terms, it is as if a prime minister had discovered the Duke of Edinburgh were conducting a liaison with a woman high up in Al Quaeda. In those circumstances, would it not be reasonable for the prime minister to wish to obtain proof to enable him to warn the monarch? This is the only crime of which Richelieu stands accused.

Richelieu at the Siege of La Rochelle

In ‘real life’ he was guilty of more, and his intelligence network of agents was every bit as widespread and dangerous as Dumas claims. There is no space here for a proper, detailed study of the man, but in simple terms his major goal was to make France great – and in this he was outstandingly successful. He saw only three obstacles in his way: the growing might of Spain, the discontent of the princes – and the weakness of the King. It was the way in which he tackled these three things that made him so many enemies. In In the Name of the King Bernadette was right when she talks about plots and conspiracies against him as simply a normal part of life.

Our concern here is with only the two most significant, and in In the Name of the King we see André de Roland exercising his unfortunate knack of being in the wrong place at the wrong time by managing to embroil himself with both of them.

The Soissons Rebellion

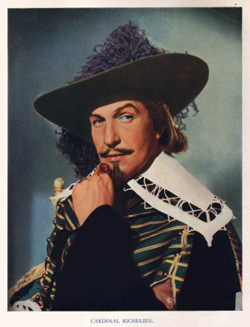

The ‘Soissons Rebellion’ is the name given to the uprising led by the so-called Princes de la Paix, operating from the Duc de Bouillon’s stronghold in the Sedan. The Sedan was at that time an independent principality, dangerously placed on the border of the Spanish Netherlands, and formed a natural magnet for the disaffected princes and barons who had fallen foul of the King – or Cardinal Richelieu.

Borders of France 1648-59

The key figures were Gaston, Duc d’Orléans, the King’s own brother and an inveterate plotter who could ultimately be trusted with nothing; Henri II, Duc de Guise, whose family had sided against Richelieu with Marie de Medici, mother of Louis XIII; Frédéric Maurice de La Tour d’Auvergne, Duc de Bouillon, a Protestant who had lost his position after secretly negotiating with the Spaniards in 1637 – and Louis de Bourbon, Comte de Soissons, the King’s cousin, who had already attempted to murder Richelieu in 1636.

|

|

|

|

| Duc d’Orléans | Duc de Guise | Duc de Bouillon | Comte de Soissons |

This unsavoury crew had arguably some right on their side, and their stated wish was peace with Spain in order to remove the intolerable burden of taxation from the peasantry. It is, however, equally likely that their true desire was to get rid of the upstart Richelieu, who was clearly grooming the monarch for an absolute power that would emasculate their own.

Whatever their true ambitions, they were prepared to enter into a secret agreement with Spain in order to achieve them. But while an enemy power might sweep them into Paris they could scarcely remain there without popular support, which is perhaps why they shrewdly made a figurehead of Soissons, who had been Governor of Champagne and still enjoyed considerable loyalty among the people. They also needed agents to prepare the ground in Paris itself…

One of the most important of these was the endearingly amoral Jean François Paul de Gondi, later Cardinal de Retz, who seems to have entirely escaped the attention of our heroes. His role at the time was largely limited to liaising with those dissidents already in prison and courting popularity by showering largesse among the poor, and since he has a far more significant part to play in the later history of the Fronde I shall say no more of him here. More important to André were the two men deep within the court itself – the shadowy figure of Louis d’Astarac, vicomte de Fontrailles, and the King’s own favourite, Henri Coiffier de Ruzé, Marquis de Cinq Mars.

There are no known portraits of Fontrailles, and it is easy to guess why. Readers of In the Name of the King will already know he was a hunchback, and his appearance was sufficiently unpleasing for Richelieu to have suggested he hide himself when a diplomat visited on the grounds that ‘the ambassador does not care for monsters.’ This shockingly cruel and very public insult clearly rankled with Fontrailles, and he cites it himself as a reason for his subsequent determination to bring down the Cardinal himself.

Three faces of Cardinal Richelieu

Fontrailles has left his own account of both the conspiracies in his memoirs, the ‘Relation de Fontrailles’. He makes a curiously likeable figure, a passionate atheist at a time of rampant religious hypocrisy, and I confess to being rather glad that in In the Name of the King Bernadette insists he was ‘no murderer’. In terms of allegiance he was always d’Orléans’ ‘creature’, that untranslatable French word meaning a man who belonged body and soul to his master, but his opinions remained very much his own.

Cinq-Mars is a young and ultimately tragic figure. The characters interviewed by the Abbé Fleuriot for the manuscripts that form ‘In the Name of the King’ are naturally more concerned with the effects of his disloyalty and the dangers into which they led, but as historians we must stand back and look at the bigger picture. The young Henri was introduced to Louis XIII’s court by Richelieu himself, with the definite intention that the pretty, vivacious boy should engage the interest of the sexually ambivalent King and distract him from his passion for his favourite of some years, Marie de Hauteforte. The plan succeeded beyond Richelieu’s wildest dreams and swiftly turned into a nightmare. Marie was dismissed the Court, while Cinq-Mars became first Master of the Robe, then Monsieur le Grand himself – Master of the Horse. Whether or not he also shared Louis’ bed (as Fontrailles apparently claimed), he became almost overnight the biggest threat yet to the Cardinal’s own ascendancy over the King. Richelieu had called Fontrailles a ‘monstre’, but it was Cinq-Mars who played the monster to Richelieu’s Frankenstein, and the Cardinal who now sought to destroy the rival he had himself created.

Marquis de Cinq-Mars

Poor Cinq-Mars. Whatever the sexuality of Louis XIII may have been, the young Marquis was interested only in marriage to the woman he loved – Marion de l’Orme. But the King forbade it, the King had him watched, and Cinq-Mars was in the end no more than the clichéd bird in a gilded cage. He was both immature and spoilt, but he was a young man with a life to lead, caught between the two terrible forces of the King and the Cardinal. There is no evidence of his active involvement in the Soissons Rebellion, but that he knew of it and sympathised with it is, I would contend, entirely understandable.

So the Rebellion began, and what came of it is told in the manuscript that forms In the Name of the King. André and his friends may have thought that was the end of the matter, but history knows it was only the beginning.

The Cinq-Mars Conspiracy

Much of this is told in In the Name of the King and needs no further explanation here. The conspiracy involved the ‘usual suspects’, including the Ducs de Bouillon and d’Orléans, Spanish help was again invoked, and Fontrailles was once more the crucial go-between. The only substantial difference was in the figurehead, which this time was young Cinq-Mars himself.

It was a risky thing to do, but Cinq-Mars would have felt himself more endangered than ever after the Soissons rebellion, and it could hardly have helped that Marion de l’Orme made it clear she couldn’t marry anyone so lowly as a Marquis. He needed serious rank, he needed both the King and Richelieu out of his way, and the conspiracy may have seemed to the immature 22-year-old to be the only way out.

The young Cinq-Mars

Yet I cannot make light of what he did. Ideals may have – must have – played a part, or he could not have induced the entirely honourable François-Auguste de Thou to keep silent as to his role in it, but he still signed an effective treaty with a foreign power that could and probably would have deposed his own King. The treaty discovered by Grimauld echoes the beginning of the actual document word for word, and we must accept that Cinq-Mars knew what he was doing when he signed it.

A tragedy then, even if not quite the one written in Alfred de Vigny’s novel - later adapted by Gounod into a full-scale opera. Poor boy, poor King, and poor France. The last recorded words of Cinq-Mars himself say it all – ‘Mon Dieu ! Qu'est-ce que ce monde ?’ ‘My God,’ he said. ‘What kind of world is this?’

What indeed.

The Mystery Conspirators

Rumour has named many other possible parties to these conspiracies, but evidence is thin on the ground and the Abbé Fleuriot’s manuscripts cast little new light on the matter.

The Queen seems almost certain to have been implicated in the second of them, and the Abbé’s papers confirm the account of the Comte de Brienne that she gave the conspirators a signed ‘carte blanche’ to use as they wished. However, the Comtesse de Roland appears confident in the loyalty of the Comte de Tréville, Captain of the King’s Musketeers, and in this she may well have been mistaken. The King certainly suspected him, and the Musketeer’s next military command took him well away from Paris – and into the path of a bullet.

|

|

Anne of Austria |

The Comte de Tréville |

But there were others. Bouchard and his friends in In the Name of the King are quite unknown to history, and were it not for the Abbé Fleuriot’s manuscripts we would have no reason to believe they ever existed. However, the account of Bouchard’s heritage is interesting, and certainly provides a reason for his involvement in treason.

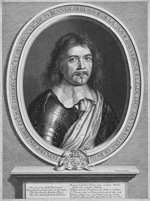

Bouchard believed himself to be the illegitimate son of the late Henri II de Montmorency, a claim given at least a spurious credibility by the ‘oddness of his eyes’. Montmorency did indeed have a highly noticeable squint, as we can see from this portrait hanging in the Musée Carnavalet:

Henri II de Montmorency

He had also been a conspirator in his own right, having raised an army in support of the incorrigible Duc d’Orléans, and been duly executed in Toulouse in 1632.

There, however, the similarity ends. Montmorency was a fine soldier, much beloved throughout France, and the general feeling (then as now) was that he was unfairly made the scapegoat for d’Orléans, whose royal blood kept him immune from execution.

Whatever the truth of it, his story illustrates the very real dangers facing even an honourable man in 17th century France. Loyalty to one faction meant always danger from another, and above every aristocratic head hung always the spectre of either assassination – or the block.

In In the Name of the King, André de Roland is to find this out for himself.